Many heat-treating processes cannot tolerate appreciable variations in steel hardenability. For an established in-control process, deviations in chemical composition and starting microstructure may result in a variety of issues including quench cracking, out-of-spec hardness, low ductility, and excessive distortion. Consequently, a hardenability tolerance should be assessed and defined for all new processes to ensure incoming material is properly controlled without being over specified.

Hardenability defined

Hardenability is often used synonymously with “end-quench” or “Jominy” hardenability, a reference to a standardized test that quantifies the hardness of a steel as a function of distance from an austenitized and water-quenched surface [1, 2]. This test has both beneficial and detrimental aspects. It is beneficial in that it allows the chemical composition variation of the raw material (e.g., bar or billet) to be characterized for quality control purposes with relative ease, but is detrimental in that it is limited in translating those results to components processed through a specific heat treatment process. As a result, for the remainder of this discussion, hardenability will be defined generally as the suppression of ferrite/pearlite formation upon cooling from austenite [1]. This definition encompasses those additional effects that are directly dependent on a specific heat treatment process.

Chemical and microstructural influences

Chemical and microstructural influences

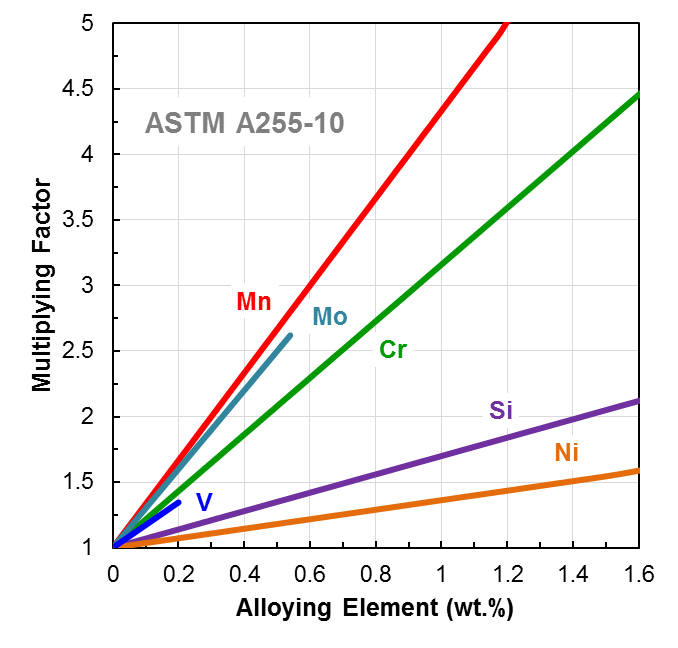

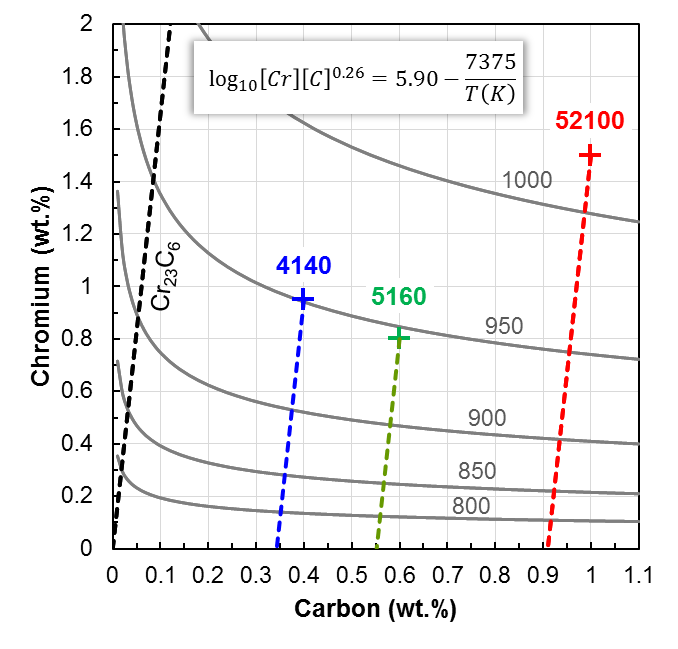

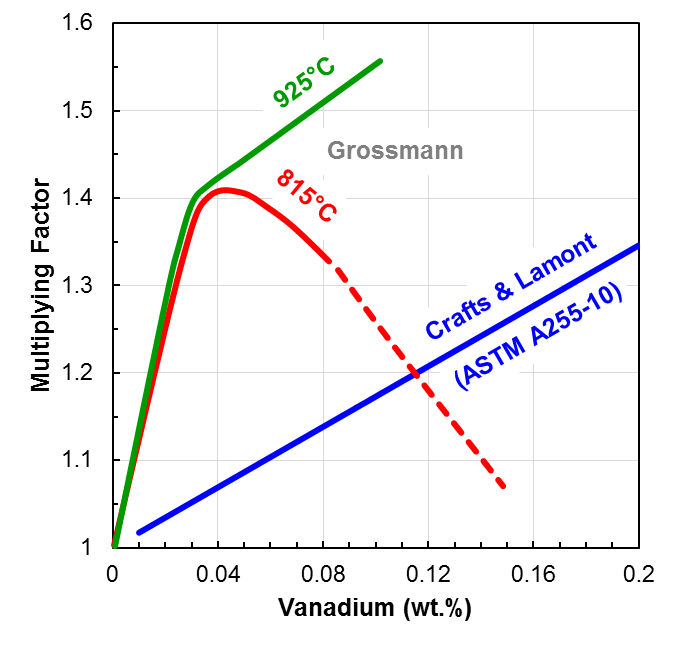

Chemical effects on hardenability are typically calculated using chemical ideal diameter (DI) – which is defined as the diameter in which the center of a round bar contains 50 percent martensite when quenched from austenite [3]. Grossmann used brine for his quenchant, but ideal diameter typically assumes an “ideal” quench rate, which is infinite [3]. Figure 1 shows the effect of different alloying elements on hardenability through multiplying factors used to calculate DI. The danger with this multiplying factor comparison is that the data represent only one austenite grain size (ASTM grain size 7) and does not take into consideration effects related to the form of the alloying elements in the steel.

Conclusion

Fraction of alloy carbides dissolved upon austenitizing may have a significant influence on hardenability, thus requiring careful monitoring of the starting microstructure as well as the chemistry. Each heat-treatment process should be evaluated to determine its acceptable hardenability range to remain a capable process. Influence of both variation in microstructure and chemical composition should be examined independently, if possible.

References

1. R.E. Reed-Hill and R. Abbaschian, Physical Metallurgy Principles, ed. 3, 1992.

Standard Test Methods for Determining Hardenability of Steel, ASTM A255-10 (reapproved 2014), ASTM International, Oct. 2014.

2. M. A. Grossmann, Elements of Hardenability. American Society for Metals, 1952.

3. M. F. Ashby and K. E. Easterling, “A First Report on Diagrams for Grain Growth in Welds,” Acta Metallurgica, vol. 30, pp. 1969-1978, 1982.

4. B. Garbarz and F. B. Pickering, “Effect of Vanadium and Austenitising Temperature on Hardenability of (0.2-0.3)C-1.6Mn Steels With and Without Additions of Titanium, Aluminium, and Molybdenum,” Materials Science and Technology, vol. 4, pp. 117 126, 1988.

5. B. Garbarz and F. B. Pickering, “Effect of Austenite Grain Boundary Mobility on Hardenability of Steels Containing Vanadium,” Materials Science and Technology, vol. 4, pp. 967 975, 1988.

6. H. Adrian, “A Mechanism for Effect of Vanadium on Hardenability of Medium Carbon Manganese Steel,” Materials Science and Technology, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 366 378, 1999.

7. H. Adrian and R. Staśko, “The Effect of Nitrogen and Vanadium on Hardenability of Medium Carbon 0.4% C and 1.8% Cr Steel,” Archives of Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 69 74, 2008.

8. C. Fossaert, G. Rees, T. Maurickx, and H. Bhadeshia, “The Effect of Niobium on the Hardenability of Microalloyed Austenite,” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 21 30, 1995.