In this column, I will discuss tempered martensite embrittlement and its primary causes.

Introduction

Once a part has been quenched, it must be tempered. This accomplishes two things. First, it relieves the thermal and transformational stress from quenching. Second, it transforms the hard, brittle martensite to the tougher tempered martensite. For high alloy steels, it may also convert any residual retained austenite to tempered martensite or bainite.

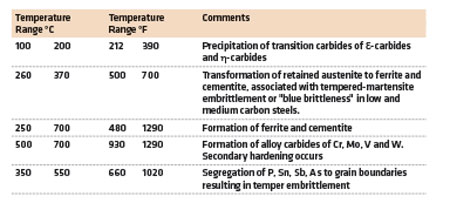

Toughness increases as the part is tempered above 150°C. In general, as the toughness increases, the hardness decreases. For high hardness applications, the tempering temperature is kept low, usually between 150-200°C. The martensite partially decomposes and forms very fine carbide precipitates [1]. The precipitates that form are transition carbides of epsilon-carbide (ε-carbide) and eta-carbide (η-carbide) [2]. They are not cementite. There is a small increase in toughness, but the matrix remains hard.

When steels are tempered between 200-350°C, the martensite precipitates cementite (χ-carbide) and any retained austenite transform to ferrite and cementite. These carbides are coarse and occur within the plates or laths of martensite. The retained austenite begins to transform above 200°C [3]. There is a slight decrease in toughness associated with tempering in the range of 250-400°C called tempered martensite embrittlement. The typical tempering reactions in steel are summarized in Table 1.

Tempering in the temperature range of 260-370°C (500-700°F) generally causes a decrease in toughness. This is observed by a reduction in the Charpy V-Notch impact toughness or the plane-strain fracture toughness (KIc). This decrease in toughness is referred to as tempered martensite embrittlement (TME) [5]. Another type of embrittlement, called temper embrittlement (TE), may develop in steels tempered above 425°C (800°F). It is often called 350°C or 500°F embrittlement.

Mechanism

A primary mechanism of TME involves the precipitation of cementite (Fe3C) at prior austenite grain boundaries and interlath regions. As martensite undergoes tempering, films of retained austenite within laths partially decompose. The resulting cementite precipitates, often in the form of platelets or continuous films, act as stress concentrators and weaken local microstructure. Cementite formed in this regime is typically coarser than that produced by lower-temperature tempering, increasing susceptibility to brittle fracture [6].

A secondary mechanism involves the stability of retained austenite. As tempering progresses, retained austenite loses carbon due to cementite precipitation, becoming mechanically unstable. Under applied stress, it can transform into untempered brittle martensite. The volume change associated with the martensite transformation can contribute to cracking, or high residual stresses, especially when adjacent to cementite films or prior austenite grain boundaries [7].

Certain alloying elements such as silicon or molybdenum help inhibit TME by retarding cementite precipitation and raising the critical temperature for embrittlement. Elements such as phosphorus and nitrogen tend to segregate at prior austenite grain boundaries, further reducing toughness by promoting intergranular cracking. Manganese and chromium can also play complex roles, influencing both carbide morphology and austenite stability [6] [8].

Influence of Processing Parameters

The amount of embrittlement is affected by the initial microstructure, cooling rates, and tempering schedule. Oil-quenched structures with less retained austenite are less prone to severe TME than air-cooled steels with high retained austenite fractions. Rapid induction heating and cooling during tempering can suppress the formation of retained austenite, which in turn, suppresses the tempered martensite embrittlement. Prolonged tempering, even at sub-critical temperatures, can coarsen carbides and trigger TME [6].

Conclusion

Tempered martensite embrittlement (TME) reduces the toughness of steel when tempering in the range of 260-370°C (500-700°F). The mechanism of embrittlement is thought to be due to the formation of interlath cementite precipitation due to partial decomposition of retained austenite films. Impurity segregation such as phosphorus to prior austenite grain boundaries can aggravate the embrittlement. Alloying elements such as silicon can retard cementite formation and stabilize the retained austenite present.

Should there be any questions on this article, or suggestions for further articles, please contact the editor or the author.

References

- D. L. Williamson, K. Nakazawa and G. Krauss, “A Study of the Early Stages of Tempering in an 1.22%C Alloy,” Met. Trans. A, vol. 10, pp. 1351-1363, 1979.

- K. H. Jack, “Structural Transformations in the Tempering of High Carbon Martensitic Steel,” ISIJ, vol. 169, pp. 26-36, 1951.

- D. L. Williamson, R. G. Schupmann, J. P. Materkowski and G. Krauss, “Determination of Small Amounts of Austenite and Carbide in a Medium Carbon Steel by Mossbaur Spectroscopy,” Met. Trans. A, vol. 10, pp. 379-382, 1979.

- ASM International, “Introduction to Steel Heat Treatment,” in Steel Heat Treating Fundamentals and Processes, vol. 4A, J. Dossett and G. E. Totten, Eds., Materials Park, OH: ASM International, 2013, pp. 3-25.

- G. Krauss, Steels – Processing, Structure, and Performance, 2nd ed., Metals Park, OH: ASM International, 2015.

- R. M. Horn and R. O. Ritchie, “Mechanisms of tempered martensite embrittlement in low alloy steels,” Met. Trans. A, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1039-1053, 1978.

- V. K. Euser, D. L. Williamson, K. O. Findley, A. J. Clarke and J. G. Speer, “The Role of Retained Austenite in Tempered Martensite Embrittlement of 4340 and 300-M Steels Investigated through Rapid Tempering,” Metals, vol. 11, p. 1349, 2021.

- H. Bhadeshia and R. Honeycombe, Steels: Microstructure and Properties, London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011.