Industrial kilns are an important component in the heat-treat industry, so it’s imperative that they are designed and built to exact specifications.

Ceramics is the quintessential building block of many industries, and Harrop Industries, Inc. has been supplying kilns and other ceramic products to a wide range of areas for more than a century.

“We are strictly a kiln designer and kiln builder for the ceramic industry,” said Dr. Jim Houseman, CEO of Harrop Industries, and the third in the company’s storied history. “Our primary product line, if you want to call it that, or services, is we’re a design-build contractor of industrial kilns for commercially producing ceramic products. We want to be a high-class supplier of application-engineered kiln systems. We’ve been a supplier to the industry for over 100 years, and we enjoy the partnerships we’ve developed with established traditional companies as well as new startups.”

Knowing ceramics

The company prides itself in knowing everything possible about drying and firing ceramics, and Houseman said that has sparked an organic growth through the years.

“Our growth has really come from the different application needs of our clients,” he said. “We don’t profess to be a materials research company. We leave that to the scientists, but we’ve evolved in our designs as we’ve seen the need of more nontraditional ceramic products being developed around the country.”

Metal heat-treaters, according to Houseman, are a big part of the industries that Harrop serves.

“All those furnaces they use are lined with ceramic refractories,” he said. “And we count refractory manufacturers as some of our best clients. They need to develop new refractories to handle these exotic alloys and processing areas in the metals industry. They need better refractories to line ladles and heat-treating furnaces and whatever. And we are a supplier of these engineered kilns that go to the refractory manufacturers.”

Custom built, every time

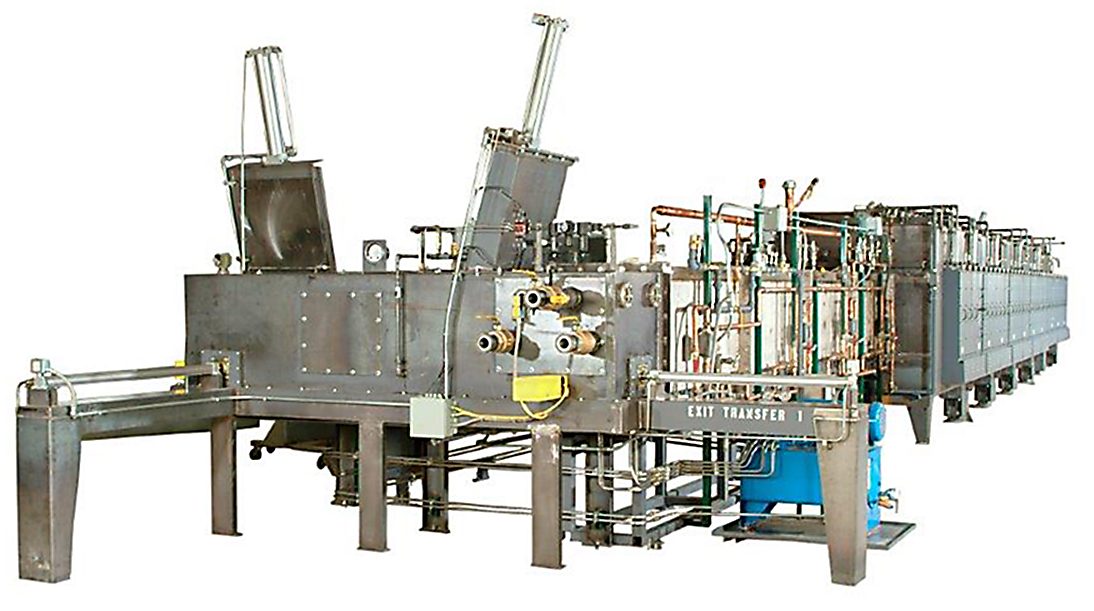

Harrop doesn’t have a product catalog, according to Houseman. The company’s goal is to build to specs exactly what its customers need.

“First, we have to ascertain what their end goal is, and, for us, we’re beyond R&D, but the typical application will come when a company has developed a product that they’ve taken out of the laboratory successfully and is looking to scale up to make a commercially available product,” he said. “This can, a lot of times, start in building prototypes or getting into pilot plant development. A number of these companies — in the past 20 years anyway — are not traditional ceramic manufacturers and know very little about how to process ceramic products. So, we work with them to mutually educate each other in how ceramics behave and how they may have to be handled as well as the firing process to make viable products.”

To help customers accomplish their goals, Harrop maintains a 12,000-square-foot developmental and testing laboratory in its Columbus, Ohio, facility, according to Houseman. This laboratory has about 19 different types of kilns used for prototyping work and test firings for clients to help them develop the profile or the process needed to make products on a commercial scale.

“Once we go through that, we then will — from our overall experience in this business — develop an industrial size kiln concept for them,” he said. “Then we go through a bidding process and write specifications for it. That’s how we approach our potential clients. We have no catalog. We have no price lists. It’s all application engineered.”

Harrop’s technicians can conduct standard ASTM compliance testing or customized thermal testing of raw materials and ceramic components. The thermal and physical behavior of ceramics can be evaluated using such techniques as thermal analysis, psychometric drying, thermal gradient testing, dilatometry, and sintering studies. Harrop offers a broad range of firing services from bench-scale testing to pilot-plant production to evaluate the drying and firing behavior of industrial ceramics.

Pushing the envelope

The experts at Harrop are always pushing the envelope of the world’s ceramic needs, and the company has been supplying kiln systems for firing high-purity ceramic powders used in lithium ion batteries for electric vehicles as well as other types of storage batteries, according to Houseman.

“We worked with clients who, instead of needing two pounds of this material a month, they need 75 pounds an hour,” he said. “You really have to get involved in the materials handling aspect of feeding the kilns and taking material away. A lot of our work is really how to integrate a high-temperature process into an integrated manufacturing process. These applications must make economic sense for the client.”

Houseman is quick to point out that Harrop is not only well established, but it is consistent and reliable on many levels. It’s been a private company since the beginning, and its roots have been in the same city, but he said Harrop’s best accomplishments rest in having satisfied clients and repeat business.

“Probably 85 to 90 percent of our revenue is on repeat business, but being in heavy capital equipment, our current clients today may not be a client again for five years,” he said. “We have a number of clients that we’ve dealt with for 40, 50, 60 years. Their needs have changed. Their requirements have changed, but we’ve had the opportunity to do business with them as their market needs have changed.”

As the markets have changed through the years, it was imperative that Harrop changed with them in order to stay viable as it enters its second century of business.

Opened its doors in 1919

Harrop Industries began life in 1919 as Carl B. Harrop Engineers when it was founded by Carl Harrop, a professor in the ceramic engineering department at The Ohio State University.

In 1918, Harrop was granted a patent on a new type of car tunnel kiln, a device for firing ceramics in a continuous process that saved substantial energy over the traditional batch firing methods.

“Due to his travels during World War I to Europe, he discovered that the Germans were processing ceramics in a much more energy-efficient manner than we were doing here in the United States, and that was by continuous firing of ceramics,” Houseman said. “He came back and started promoting this within the ceramic industry and it just took off like wildfire.”

Nine years of successes later, the company incorporated as Harrop Ceramic Service Company, with Harrop as president until his death in 1934. In 1936, Harrop’s second CEO, George D. Brush, a civil engineer who had worked for Harrop since 1923, took over. When Brush retired in 1978, Houseman stepped in. The company officially changed its name to Harrop Industries, Inc. in 1981.

Along with its testing facility, Harrop’s current location in Columbus, Ohio, boasts 17,000 square feet of office space and 36,000 square feet of fabricating shop.

Continued advancement

Harrop continues to look for ways to advance the field of ceramics, and in doing so, commercialized a firing process called Microwave Assist Firing that can be used to more uniformly heat materials, according to Houseman.

“Microwave energy, of course, is a way to impart thermal energy into materials,” he said. “And typically, ceramics are heated from the outside in just as metals are. But with the use of microwave energy, we can actually start heating materials from the inside out.”

Many ceramic products made today have complicated geometric shapes, so traditional methods of heating those products from the outside in would often cause unwanted temperature differentials, according to Houseman.

“What we’ve found is that we can use microwaves on certain materials to heat them from the inside and keep the temperature uniformity a lot better, and the quality of the product can be much higher using it,” he said.

Houseman expects Harrop’s kiln designs to be at the forefront of many industries as more exotic materials are developed, particularly in the transportation and energy sectors.

“We’re biased of course, but we think ceramics have got a growing place in the industrial field,” he said.

MORE INFO harropusa.com